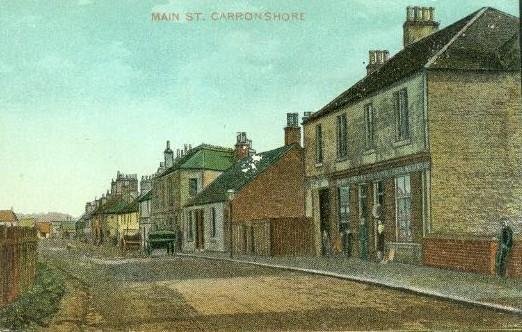

Main Street Carronshore c. 1910

20890 Pte Thomas Jardine

11th Bn Royal Scots

(The Lothian Regiment)

Killed in Action, 20 October 1916

Thomas was the third child of John Jardine and his wife, Grace, nee Sorbie. John (snr) was a baker, born in Holytown, Lanarkshire. Grace hailed from nearby Stonehouse . Thomas’s father was a baker and his mother was a dairy maid.

Between 1884 and 1911, the family gradually moved from the west of Scotland to the east, from Glasgow and Stonehouse through Kilsyth and Stenhousemuir and eventually arriving in Blackmill, Carronshore. The family had moved east to Kilsyth (1891 census) and moved on to Larbert’s Main St Wilson's Buildings before moving through to Carronshore.

Carronshore School

Main Street Carronshore ca. 1910

The Edwardians of the 1900’s were aware of the lowering storm clouds epitomised by the impact of Dreadnought competition between Britain and Germany. In 1903 Erskine Childers wrote “The Riddle of the Sands”, a spy novel that anticipated the invasion of Britain by the German army. The novel focused the public on what appeared to be the menace of Germany by invasion, and was an element of the bourgeoning naval rivalry between Germany and Britain. was very much a part of the path to war between the Entente nations and the Central Powers.

Stenhousemuir ca. 1910

Bothies, Carronshore

By 1911 the family had moved further west to Carronshore. The development of mining in the carselands to the east meant that settlements in Carronshore and around Carronshore provided commercial opportunities that serviced demand for various trades such as the bakery owned by the Jardine family..

The 1911 Census shows the family in Blackmill, Carronshore, with paterfamilias John still working, as a foreman baker. The list clearly reflects the foundry industry that was central to the working life of Stenhousemuir and Carron reflecting the influence of the Carron works.

The family are shown on the 1911 census as Mary aged 17 is shown as a domestic servant.

John (jr), 24 is a Range Stove Fitter,

Thomas, 22 is a boiler moulder and William, 19, is a blacksmith.

James, the youngest son aged 14 is an Engineer.

Records show that Isabella Jardine (Bella) married James Dempster on 23 June 1905, the oldest of the children. James was a carriage driver but sadly, James died aged 32 on 9th December 1909.

Bella subsequently re-married, marrying the impressively named John McCracken MacDonald, a coal miner from Coatbridge. Despite the sad loss of James, the family continued to prosper.

Following the death of James, neither Bella nor Grace are shown on the census as having an occupation. John snr aged 47, is still a baker, but appears to be involved in a baking society, presumably a group of bakers.

The Jardine family had been set for the future, but the future was increasingly uncertain. The call to arms meant that young men of Thomas’ age would be swept up in the patriotic adventure sparked by the Sarajevo assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and the declaration of war in 1914. The social pressure on young men of age to enlist was significant and Thomas Jardine attested at Stirling on 11 March 1915.

Attestation papers of Thomas Jardine

As a Carronshore man, it may seem a little odd that Thomas enlisted in the Royal Scots. Most of his peers were joining the 7th Argylls. However there is a possible explanation in that some years earlier, Thomas’ older brother John tried to rejoin the Argylls but irregularities in the attestation process resulted in John being given a short sentence due to “irregularities”, and “demotion” to a Territorial K.O.S.B. battalion. It seems likely that Thomas, the brother of John Jardine joining the 7th Argylls may have been a trifle embarassing

Appointment of Thomas Jardine to the Royal Scots at Stirling - 11 March 1915

France

Thomas’ battalion, the 11th (Service) Battalion (the Lothian Regiment), formed at Edinburgh, August 1914 and became part of the newly formed Scottish 9th Division. Advance parties left the Bordon Camp in Hampshire, 8 May 1915, with the three infantry brigades of the 9th Division crossing from Folkestone to Boulogne, a move completed by 15th May with the Division concentrating at St Omer, the Division occupied billets south of Baillieu, with Thomas Jardine’s 27th Brigade billeted around Noote Boom.

The units of the Division subsequently underwent familiarisation in the front-line trenches under the tutelage of the 6th Division to help prepare the men for the fighting to come. As part of this process Thomas and his comrades received constant instruction in bombing, the only reasonable method to attack without exposure to direct fire.

The established pattern for trench routine was for a man and his section to spend 4 days in the front line, then 4 days in close reserve and finally 4 at rest, although this varied enormously depending on conditions, the weather and the availability of enough reserve troops to be able to rotate them in this way. That pattern was repeated correspondingly for divisions, brigades and battalions.

The pressure from the on the British to support the French Army, hard pressed and suffering significant casualties along an extended front line meant that the General Staff under Douglas Haig were pressured by the French to relieve the French armies to the South, but mostly to demonstrate a willingness to become a siginificant force. Whilst the build-up of the British Army in France was growing apace, the pressure from the French to assist the British was increasing. The need to demonstrate willing.

As a consequence, Haig’s army was required to go on the offensive and the decision was that the B.E.F. would attempt to drive back the Germans to the south on ground that that was not of its own choosing and at a time not of its own choosing at Loos.The Allied decision was that a large-scale offensive should take place at Loos, a mining area which was largely flat but dominated by high ground on a relatively prominent ridge line.

“The Battle of Loos took place from 25 September to 8 October 1915 in France on the Western Front, during the First World War. It was the biggest British attack of 1915, the first time that the British used poison gas and the first mass engagement of New Army units. The French and British tried to break through the German defences in Artois and Champagne and restore a war of movement. Despite improved methods, more ammunition and better equipment, the Franco-British attacks were largely contained by the Germans, except for local losses of ground. The British gas attack failed to neutralize the defenders and the artillery bombardment was too short to destroy the barbed wire or machine gun nests. German tactical defensive proficiency was still dramatically superior to the British offensive planning and doctrine, resulting in a British defeat.”

27th Brigade was ordered to support this apparent breakthrough. However its units met with mixed fortunes. 12/Royal Scots advanced with few losses and reached Pekin Trench by 8.45am. 11/Royal Scots lost direction and in correcting it ran into a deep wire entanglement, where they were caught by machine-gun fire and virtually wiped out. 10/Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders heard that Pekin Trench was already strongly held, and halted in Fosse Alley.

The 27th Brigade moved into the front line on the evening of 20th May and was it was relieved on 22nd May by 26th Brigade. By 31st May all detachments of 9th Division had received at least some experience of the trenches. On 26 June, 9th Division were ordered to relieve 7th Division in the line near Festubert, and accordingly 26th and 27th Brigades took over the front line on the nights of 1st and 2nd July with the 28th in reserve.

Loos - “Tower of London” part of the mining complex, and dominating the battlefield.

The battle of Loos was the first genuinely large scale British offensive but still had a supporting rather than key role in the large-scale and predominantly French-led l and French driven Third Battle of Artois. British appeals that the ground over which they were being called upon to advance was wholly unsuitable were ignored by the French as the major partner in the battle

Schematic of Loos battlefield (Long. Long, Trail. - Chris Baker)

9th Division took over the 1st Division trenches east of Vermelles which would be the scene of the Division’s first battle, Loos, fittingly pronounced “loss”. The much awaited operation to break the German line would begin on 2nd September , ending on 8th October.

The Divisional history reflects that the plan for the battle of Loos was too ambitious with the author, John Ewing M.C., commenting that it was “impossible to condone the reckless optimism that shaped the plans for the Battle of Loos, which revealed a disposition to underrate the adversary”.

The battle was aimed at addressing the gap between the right of the British forces and on the left those of the 10th French Army. The battle was also historically noteworthy for the first British use of poison gas.

On 2nd September 1915, 9th Division took over the 1st Division trenches east of Vermelles which would be the scene of the Division’s first battle, Loos, fittingly pronounced “loss”.

Thomas Jardine’s 11th Royal Scots, part of 27th Brigade, was in support of the two assaulting brigades.

The map below shows 11th Royal Scots top left behind the 28th and 26th Brigades.

Source - Lon, Long, Trail - (Source Chris Baker)

9TH Scottish Division assaulting at Loos

Infantry assault across plain toward ridge line, Loos

Loos was to be the first genuinely large-scale British offensive action of the Great War, but remained a supporting role to the larger French attack (Third Battle of Artois.). British appeals that the ground over which they were being called upon to advance was wholly unsuitable were rejected.

Loos was a mining area, complete with miners’ cottages (French “cities”) and slag heaps, admirably adapted for an obstinate and protracted defence. On a much smaller scale, the area around Loos would have been familiar to Thomas Jardine who lived in a mining area. Thomas lived amongst mining folk, with friends who were miners and who lived in a mining village.

The task of 9th Division was to assault the German lines, with two brigades (26th and 28th) with Thomas Jardine’s 27th brigade in reserve: the task of the Division was to break through the first and second lines of the German defences from Haisnes in the north to Hulluch in the south and to take the settlements beyond.

The role of 27th Brigade was to support the assault by the two brigades on the ridge-line across the exposed valley. Much attention was focused on the mechanics of getting the troops into a position whereby they would be able to assault the German troops. Although attention had been paid to destroying the wire protecting the German lines. In the event, after 4 days preparation the artillery barrage was still relatively ineffective. The breakthrough and day one revealed the objectives had not been effectively destroyed. Attempts to take the German positions continued, but continued to be ineffective. The attacks continued but no break through was effected.

According to the view of the officer writing the Divisional history of the battle

“The second attack was was an offence against a well-understood military principle that was too often neglected in the warfare in France; When men have failed to in an attack, it is generally futile to send other men to make another attack in the same way… The hope of smashing, by artillery bombardment of 30 minutes, defences that had remained intact afterfour day’s bombardment, betrayed an almost unbelievable optimism. The most feasible way was to send a part of 27th Brigade to follow behind 26th Brigade. The battle progressed with the British units being doggedly forcing their way as best they could in an attempt to force their way through.

The 27th Brigade moved into the front line on the evening of 20th May and was it was relieved on 22nd May by 26th Brigade. By 31st May all detachments of 9th Division had received at least some experience of the trenches. On 26 June 9th Division were ordered to relieve 7th Division in the line near Festubert, and accordingly 26th and 27th Brigades took over the front line on the nights of 1st and 2nd July with the 28th in reserve.

A standard pattern for trench routine was for a man and his section to spend 4 days in the front line, then 4 days in close reserve and finally 4 at rest, although this varied enormously depending on conditions, the weather and the availability of enough reserve troops to be able to rotate them in this way. The same pattern of “units of three” was repeated for each level from platoon to division.

Loos was to be the first genuinely large-scale British offensive action but remained in a supporting role to the larger French attack (Third Battle of Artois.). The British appeals that the ground over which they were being called upon to advance was wholly unsuitable were rejected.

On 2nd September 9th Division took over the 1st Division trenches east of Vermelles which would be the scene of the Division’s first battle, Loos, fittingly pronounced “loss”. The Divisional history reflects that the plan for the battle of Loos was too ambitious with the author, John Ewing M.C., commenting that it was “impossible to condone the reckless optimism that shaped the plans for the Battle of Loos, which revealed a disposition to underrate the adversary”[i].

The battle would address the gap between the right of the British forces and the left of the 10th French Army. The battle is also historically noteworthy for the first British use of poison gas.

The objectives of Jardine’s brigade were the Hohenzollern Redoubt on the fortified ridgeline which dominated the featureless plain below, on and around the trench systems at the base of the escarpment.

The plan involved Thomas Jardine’s 27th Brigade in reserve, supporting the assault by 28th and 29th Brigades on Loos and the ridge overlooking the battlefield which the assaulting British soldiers would advance. 9th Division would assault the German lines, with two brigades (26th and 28th) with Thomas Jardine’s 27th in reserve. Loos was a mining area, complete with miners’ cottages and slag heaps, admirably adapted for an obstinate and protracted defence. On a much smaller scale, Loos would have been familiar to Thomas Jardine, and many of whose friends in Carronshore will have been miners in the pits around Carronshore. We know that Alexander Baird of serving with 8th K.O.S.B. was present on the same battlefield

9th Division took over the trenches east of Vermelles on 2nd September which would be the scene of the Division’s first battle, Loos, fittingly pronounced “loss”. The Divisional history reflects that the plan for the battle of Loos was too ambitious with the author, John Ewing M.C., commenting that it was “impossible to condone the reckless optimism that shaped the plans for the Battle of Loos, which revealed a disposition to underrate the adversary”.

[i] xxxx

[ii] xxxx

The formidable Hohenzollern Redoubt

Here’s a thing…My grandfathers both survived the Great War. Two (at least) of my great Uncles died on active service including Hubert who died on the Somme and Septimus who died at Suez.

By the way:

Photographs taken in the Great War now appear to have become protected property, and charges made for reproduction. I’m sure as hell that the people who have “bought the rights” to these photographs had absolutely nothing to do with making these photos. So, damn them all. These are the histories of these men (and women) and I believe that they are the property of the men in the photographs and not the smug, acquisitive gits that attempt to prevent history breathe.

tie up LOOS AND MOVE ON TO pASCHENDALE. FAR MOR INTERESTING…….

tHE SALIENT

Throughout the Great War, the notion of the “Big Push” which would create Victory was the hope, and the greatest disappointment. In 1916, the Big Push was always coming, and for the British and Empire armies that breakthough was going to be the Battle of the Somme.

The reality was that Great War would not be a single breakthrough but the grinding down of the armies, a war of attrition and grinding horror. For the French, that breakthrough would be Verdun, which ended in a stalemate. And for the Germans it was the Kasierschlacht, the 1918 March offensive which so nearly succeded. But the reality was the bitter, awful death of a million wounds that eventually wore down the German armies, and the blood price was paid. The war was to be the bloody grinding down of men and the reality that the most coutries with the best access to reources and materiel, and the greatest economical strength.

For Britain and its Empire the Battle of the Somme was one of the almost imperciptible point where the military efforts of the Allies and those of the Central Powers began to change.

The Battle of the Somme began on 1st July 1916 and 11th Royal Scots were in reserve at the feature known as Copse Valley, not shown on map below.

The Somme

The Somme offensive which began on 1st July 1916 looms over the story of the Great War. For the Empire Forces fighting in France, the Somme battle of 1 July to 18 November 1916 was a, if not the, defining point for the British Army. It was arguably the worst of the fighting, the epitome of despair and savagery, an endless graveyard.

Private Thomas Sorbie JARDINE Royal Scots 11th Battalion Service Number: 20890 Date of Death: 22 October 1916 Age at Death: 28 Family: Son of John and Grace Jardine, Blackmill, Carron

Nose. These had just been taken as a result of the efforts of South African regiments in appallingly muddy conditions. It was, wrote their historian, “the most dismal of all the chapters of the Somme”. When the 11th Royal Scots moved into position, the battalion war diary noted: “The number of GERMAN dead lying about was very noticeable. There must have been 300 dead bodies about the NOSE.” The task of the 11th battalion until it was relieved on 24 October was to consolidate the position they held. The soldiers called this “shaping the mud pie” which gives some idea of the conditions at this time. At 3.30 p.m. on October 22, the Germans bombarded the Royal Scots’ support line for two hours, repeated the barrage between 7 and 9 p.m. and shelled their trenches throughout the night. According to the battalion war diary, 14 soldiers of the Royal Scots were killed on the 22nd; the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records the deaths of 25 members of the battalion on that date. Thomas Jardine was one of these casualties.

These had just been taken as a result of the efforts of South African regiments in appallingly muddy conditions. It was, wrote their historian, “the most dismal of all the chapters of the Somme”. When the 11th Royal Scots moved into position, the battalion war diary noted: “The number of GERMAN dead lying about was very noticeable. There must have been 300 dead bodies about the NOSE.” The task of the 11th battalion until it was relieved on 24 October was to consolidate the position they held. The soldiers called this “shaping the mud pie” which gives some idea of the conditions at this time. At 3.30 p.m. on October 22, the Germans bombarded the Royal Scots’ support line for two hours, repeated the barrage between 7 and 9 p.m. and shelled their trenches throughout the night. According to the battalion war diary, 14 soldiers of the Royal Scots were killed on the 22nd; the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records the deaths of 25 members of the battalion on that date. Thomas Jardine was one of these casualties.

The 27th Brigade, part of 9th (Scottish Division) were in Corps reserve at Copse Valley on 1st July, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, relieving 17th Manchesters at Montauban. SOUTH AFRICANS BITTER FIGHTING ETC